Compact Disc Mastering in the 1980s

May 26, 2025

In the mid 1980s, as the compact disc emerged as the premier high-fidelity format, Sony devised a pioneering all-digital mastering chain centred on the PCM-1630 processor and DMR-4000 recorder. Combining bit-perfect conversion, real-time error monitoring and frame-accurate editing with dedicated subcode authoring and analysis tools, this workflow ensured that every nuance of the original mix was faithfully captured and verified before pressing. This article revisits that era-defining process, detailing how each component worked in concert to deliver the pristine, reliable masters that defined a generation of digital audio.

This article examines the mid 1980s Sony PCM-1630 and DMR-4000 U-Matic mastering system, which represented the culmination of several earlier Sony audio processor and recorder configurations.

In the early 1980s, the Compact Disc was the new format for the future, that would last forever.

Mastering for

Compact Disc in 1985 and Beyond

In the mid 1980s, creating a master for the new compact disc format was an art as much as a science. Sony engineers assembled a fully digital chain that combined precision conversion, real-time error checking and frame-accurate editing into a seamless workflow. Although today we take bit-perfect transfers for granted, mastering engineers of that era relied on a suite of dedicated machines – the PCM-1630 processor, the DMR-4000 recorder and a host of supporting units – to guarantee that every nuance of the original tape made it onto CD exactly as intended.

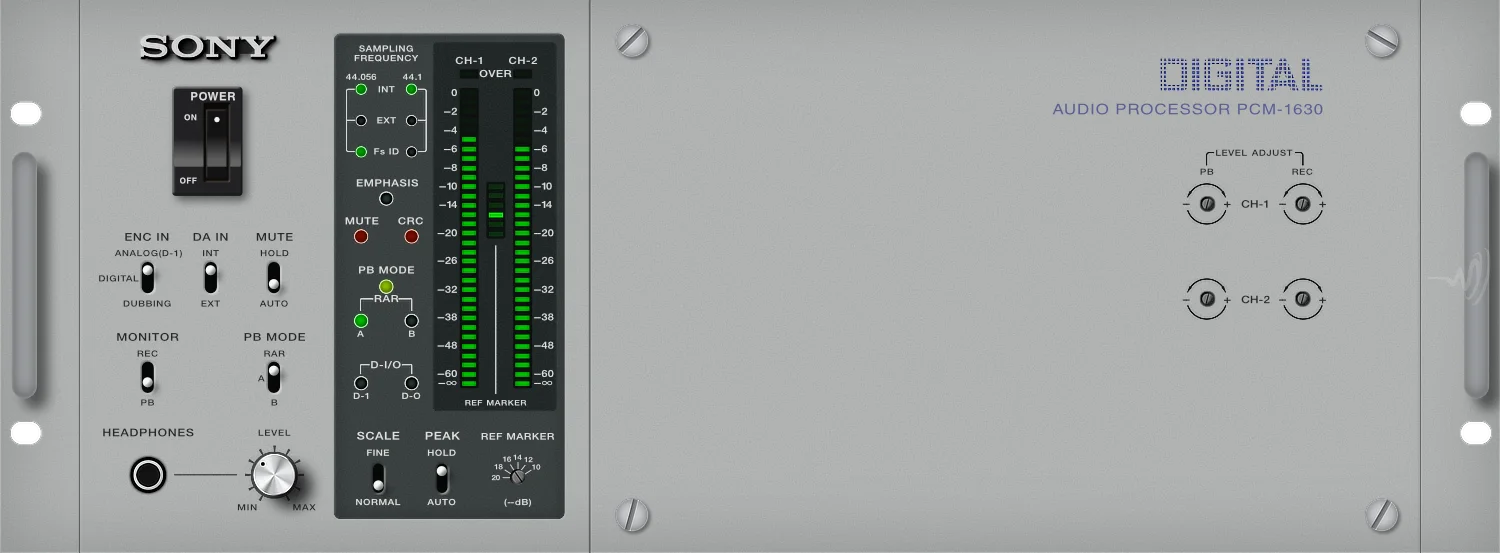

The process began in the control room, where the final stereo mix was fed into the PCM-1630 digital audio processor. Its sixteen-bit converters ran at 44.1 kHz or 48 kHz and delivered more than 90 dB of dynamic range with a flat 20 Hz to 20 kHz response. Engineers monitored levels on illuminated peak meters and switched between two independent inputs to ensure redundancy. Because the PCM-1630 used oversampling filters and low-noise analogue circuits, the resulting digital data captured the warmth and detail of the mix without audible artefact or noise.

With the processor locked to the mix, the feed went directly into the DMR-4000 digital master recorder. This was no ordinary tape deck. Housed in a sturdy U-matic transport, it carried a rotating head drum and six heads – two for erasing, two for record/playback and two for playback only. From the very first recording pass, it employed the RAW function. As the recorder laid down data it simultaneously replayed that same segment back through the PCM-1630. Any discrepancy between input and playback lit an error lamp, so the engineer could re-record immediately. In an age when memory chips were expensive and tape could glitch, this real-time verification was revolutionary.

Once the recording passed RAW scrutiny, engineers switched the deck into playback mode and enabled RAR. The recorder read each track twice in succession and sent both copies to the PCM-1630, which automatically chose the cleaner rendition for monitoring. This double-read arrangement protected against tape drop-outs or mechanical imperfections and gave confidence that the master would play back flawlessly.

Next came the delicate art of defining track boundaries and generating the subcode that told CD players where each track and index began. The DAE-3000 digital audio editor slipped between processor and recorder. With its transport controls and preview output, it allowed frame-accurate cuts, crossfades and level adjustments directly in the digital domain. Engineers could audition edits under RAR playback to ensure seamless joins before committing them to tape.

For subcode authoring, the DAQ-1000 cue editor took over. It analysed the mastered tape, auto-detecting track numbers and index points, then let the user fine-tune pause lengths and store the cue sheet in memory. Inside the unit, a dedicated PQ Generator board translated those decisions into the standard channel-formatted data required by the pressing plant. A printed copy of the cue sheet accompanied the master tape as a visual reference.

Before shipping the tape off for glass mastering, every engineer ran a final check with the DTA-2000 digital tape analyser. Clamped to the PCM-1630’s output, it scanned for CRC and parity errors, mute flags and SMPTE time-code continuity. Even a single frame-level fault would force a re-record of the affected section. Only a perfectly clean pass earned a green light for pressing.

Looking back, the Sony PCM-1630/DMR-4000 workflow was a triumph of engineering and careful procedure. It married high-performance converters with real-time error-proofing, precise editing and rigorous quality control. The result was a compact disc master tape that faithfully preserved every detail of the original mix and set a standard for digital audio that still resonates today.

The Sony DAE-300 Digital Audio Editor

The Sony DMR-4000 Recorder

Ultimately, the Sony PCM-1630 and DMR-4000 mastering chain set a benchmark for digital audio quality and reliability that shaped the compact disc era; by enforcing bit-perfect conversion, real-time RAW and RAR error checks and precision editing alongside dedicated subcode authoring and analysis tools, it ensured that every master tape delivered to pressing plants captured the full depth and nuance of the original mix. And then along came DAT…